Monday, August 30, 2010

Baby Jane

Barbarella blew my mind, it really did. Immensely creative at every turn, and with marvelous scenography, it has most certainly climbed to the top of my all-time, very very favorite, movie list. Not to mention, Jane Fonda is a fox, and I don't just mean physically. Her flaxen locks and charming voice may only be upstaged by her cultured brains and spiritual brawn, and whether she is being attacked by savage childrens' toys or seduced by and ice ship captain, I continue to hold her in the highest esteem. I recently rented Jean-Luc Godard's fascinating and honestly bewildering "Tout Va Bien" (1973)_with Yves

Montand. It has to do with strikes, in this case of the 70s, which have long been an important part of French culture. When I was there for three weeks in 2000, the school teachers were on strike all of the time, with monthly strike funds given to theirs and other unions monthly. The film is about both the strikes and the intimate relationship between two individuals. I recommend it.

This is Jane Fonda. During my two week visit in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, I've had the opportunity to visit a great many places and speak to a large number of people from all walks of life- workers, peasants, students, artists and dancers, historians, journalists, film actresses, soldiers, militia girls, members of the women's union, writers.

I visited the (Dam Xuac) agricultural coop, where the silk worms are also raised and thread is made. I visited a textile factory, a kindergarten in Hanoi. The beautiful Temple of Literature was where I saw traditional dances and heard songs of resistance. I also saw unforgettable ballet about the guerrillas training bees in the south to attack enemy soldiers. The bees were danced by women, and they did their job well.

In the shadow of the Temple of Literature I saw Vietnamese actors and actresses perform the second act of Arthur Miller's play All My Sons, and this was very moving to me- the fact that artists here are translating and performing American plays while US imperialists are bombing their country.

I cherish the memory of the blushing militia girls on the roof of their factory, encouraging one of their sisters as she sang a song praising the blue sky of Vietnam- these women, who are so gentle and poetic, whose voices are so beautiful, but who, when American planes are bombing their city, become such good fighters.

I cherish the way a farmer evacuated from Hanoi, without hesitation, offered me, an American, their best individual bomb shelter while US bombs fell near by. The daughter and I, in fact, shared the shelter wrapped in each others arms, cheek against cheek. It was on the road back from Nam Dinh, where I had witnessed the systematic destruction of civilian targets- schools, hospitals, pagodas, the factories, houses, and the dike system.

As I left the United States two weeks ago, Nixon was again telling the American people that he was winding down the war, but in the rubble- strewn streets of Nam Dinh, his words echoed with sinister (words indistinct) of a true killer. And like the young Vietnamese woman I held in my arms clinging to me tightly- and I pressed my cheek against hers- I thought, this is a war against Vietnam perhaps, but the tragedy is America's.

One thing that I have learned beyond a shadow of a doubt since I've been in this country is that Nixon will never be able to break the spirit of these people; he'll never be able to turn Vietnam, north and south, into a neo- colony of the United States by bombing, by invading, by attacking in any way. One has only to go into the countryside and listen to the peasants describe the lives they led before the revolution to understand why every bomb that is dropped only strengthens their determination to resist. I've spoken to many peasants who talked about the days when their parents had to sell themselves to landlords as virtually slaves, when there were very few schools and much illiteracy, inadequate medical care, when they were not masters of their own lives.

But now, despite the bombs, despite the crimes being created- being committed against them by Richard Nixon, these people own their own land, build their own schools- the children learning, literacy- illiteracy is being wiped out, there is no more prostitution as there was during the time when this was a French colony. In other words, the people have taken power into their own hands, and they are controlling their own lives.

And after 4,000 years of struggling against nature and foreign invaders- and the last 25 years, prior to the revolution, of struggling against French colonialism- I don't think that the people of Vietnam are about to compromise in any way, shape or form about the freedom and independence of their country, and I think Richard Nixon would do well to read Vietnamese history, particularly their poetry, and particularly the poetry written by Ho Chi Minh.

Sunday, August 29, 2010

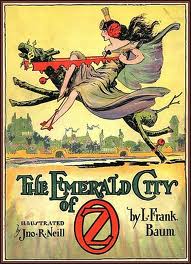

John Rea Neill

When I was about five years old my father and I ducked into a bookstore in NYC to avoid a pounding gale. Being that I was a relatively well-behaved child at the time, he permitted me to choose one book as a gift. Based on its spine, a bold yellow with thick black text, I extruded from a shelf The Wizard of Oz, by L. Frank Baum. I had not seen the Hollywood rendition of the story yet, and dubious as to my decision, a chapter book with less than a dozen pictures in it, my father suggested I peruse the book for a while, just to make absolutely certain I wanted it as my gift, that I wouldn't prefer a book with more images, seeing as I couldn't read yet, or even a book from the children's section, seeing as I was a child. After 20 minutes with the book, I remained certain of my decision, and so the book was bought, the story read to me on the many train rides taken on that trip to the North, and the tale's imagery cemented in my mind forever. My father ended up reading all of the Oz books to me, fourteen in total, along with Baum's American Fairytales, some time later.

The books and my personal history with them were not forgotten, but as I collect my own private library from my family's resources and from estate sales, I came across the series again, and have begun to examine them anew. Written for children, they are relatively quick reads, but the characters are magnificently well-imagined, and the dialogue dated yet humorous. But what is even more interesting to me as an adult artist, attempting to sharpen my discerning eye, are the illustrations. John R. Neill was commissioned to create accompanying images for the second Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz , in 1904, after Baum argued and lost contact with The Wizard of Oz's illustrator, W.W. Denslow. Since then, Neill's pen and ink Oz drawings have become what he is best known for, though he began his career in advertising.

The drawing style itself is very much of the era, with characters such as the famous Dorothy and other mortal humans, or normal animals in Oz being well-drawn but relatively innocuous, rendered in a style I associate with art nouveau. When it comes to the more whimsical personages in the story however, the overall stylistic aspects of Neill's mark-making give creatures such as cubic block animals, giant frogs, mangy lion-tiger-monkey hybrids, and my personal favorite, the patchwork girl, a very solid and enchanting quality.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)